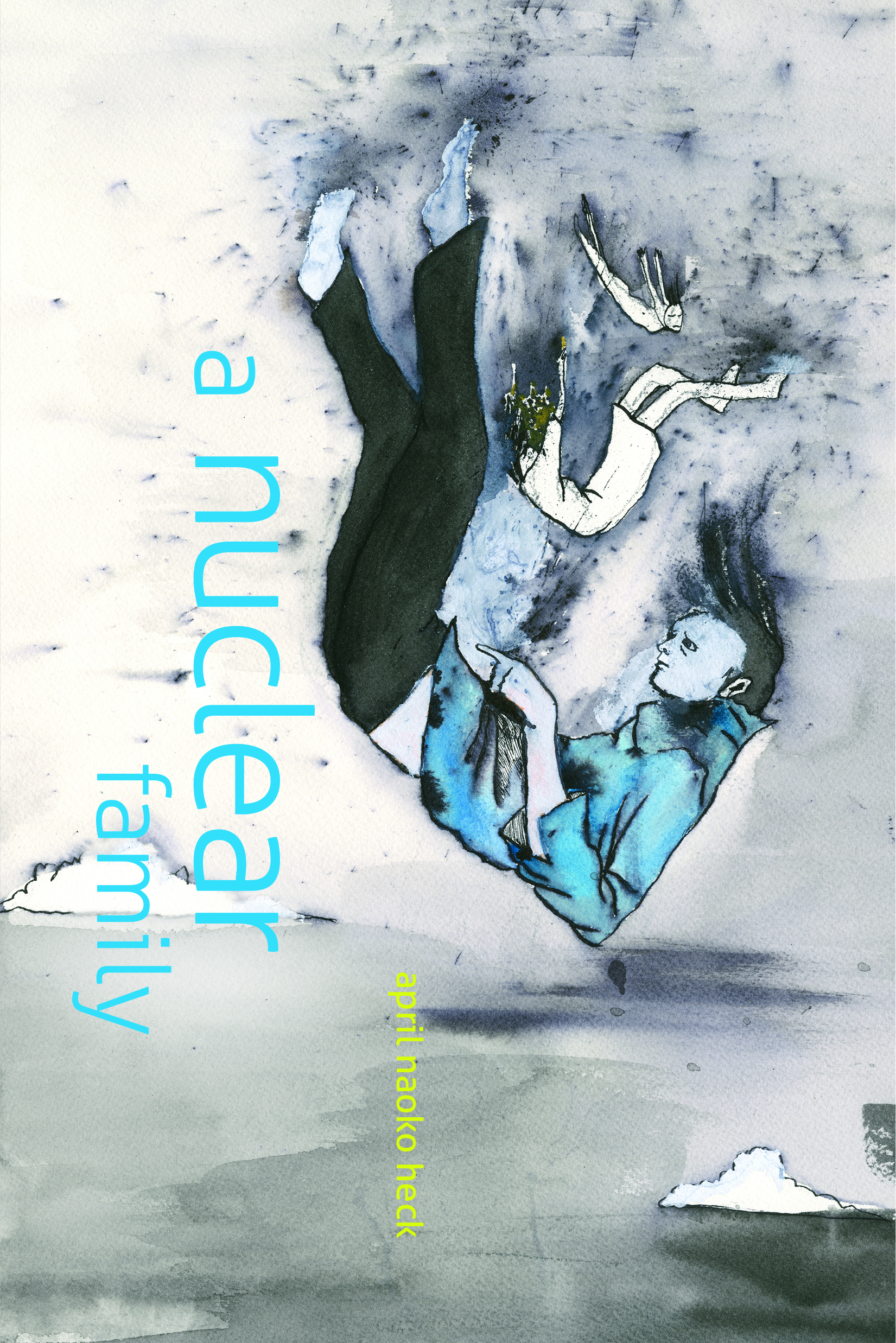

A Nuclear Family by April Naoko Heck

“Read these poems and trust this history.”— Kimiko Hahn

UpSet Press is pleased to announce the release of A Nuclear Family, April Naoko Heck’s debut book of poetry.

As we approach the 70-year anniversary of the dropping of the first atomic bomb, Heck’s timely collection explores the brink of creation and annihilation — the dawning of the nuclear age and the shaping of Japanese American identity within the shadows of WWII.

On August 6, 1945, in Hiroshima prefecture, Heck’s great-grandmother walked in a field 2.5 miles away from the blast’s epicenter. Meanwhile, 20 miles away, in the town of Otake, Heck’s mother was in the womb of her mother, presumably safe from the impending nuclear fallout.

Drawing from conversations with family members and historical research, Heck traces the footsteps of her great-grandmother, and then turns her attention westward to her literal nuclear family in poems about her Caucasian American father’s job at a nuclear power plant, as well as his later illness and passing.

As Kimiko Hahn discerns for us, “Plain horror courses beneath the surface of many of these poems — and that intensity issues from the history we know and the history we could not know because A Nuclear Family really is a poetry-memoir. And such a collection makes me realize how without art, we only have dry records. With April Naoko Heck’s poetry, we now have the burning horse, white light and black rain, a skull pulverized for medicine, a hundred Canada geese, the Ponce de Leon Motel, a frozen lake. And where horror subsides, there is a lovely tranquility. Read these poems and trust this history.”

A Nuclear Family (ISBN 978-1-937357-91-7 / $11.95 / March 1, 2014) is available for purchase on Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/Nuclear-Family-April-Naoko-Heck/dp/1937357910/.

Born in Tokyo, April Naoko Heck moved with her family to the U.S. when she was seven. Her poems have garnered an AWP Intro Journals Award, Academy of American Poets Prize, and Allen Tate Memorial Award, among other honors. Her writing appears in publications including Alaska Quarterly Review, Artful Dodge, Asian American Literary Review, Cleveland Plain Dealer, The Collagist, Cream City Review, Poets & Writers, The Rumpus, and Shenandoah. A Kundiman Fellow, she has been awarded residencies at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and Vermont Studio Center. She currently works for the NYU Creative Writing Program.

Please contact nuclearfamily@upsetpress.org for review copies, interviews with the author, and to set up readings and/or classroom visits.

REVIEWS & INTERVIEWS:

The Los Angeles Review of Books

From 1945 Japan, the book moves inward, examining Heck’s own nuclear family, experiences as a Japanese-American, and her father’s job at a nuclear power plant. The word “nuclear” is at once reminiscent of a family ravaged by war and the family as a social unit. Heck excels in juxtaposing horrific imagery with moments of simple language: “After years, she would still hold up her hands / and flutter her fingers to describe what she saw, / pale blue light dropped to the sky, / Kira-kira, she said. Twinkle, twinkle.” Bookended by violence—World War II and ten years after September 11, 2011—A Nuclear Family is a story of survival, what it means to be a daughter, and how to tell the stories we inherit. The book opens with the searing image of “fistfuls of silver / sewing needles fused / together eyeless,” and ends with the instruction to “Open your eyes.”

Review by Ansley Moon

Late Night Library Interviewed by Amanda McConnon

Here is an excerpt:

AM: Another the part of the book that deals with your father, your life together, and his death, accesses a tender side of the voice that isn’t as present throughout the rest of the book. How was writing about this subject matter different than writing the poems about Japan?

AH: Thank you for noticing that. I think the difference is in the magnitude and quality of grief I feel over these losses. I didn’t know my great-grandmother except through stories, so I don’t feel the same kind of tenderness toward her as I feel toward my father. That emotional distance is helpful in being able to control language. I often feel I don’t have enough control when I’m writing about my father because the grief is so much closer to the surface. I think tenderness is probably both an asset and a liability in poems: you need just the right amount to court but not indulge in sentimentality.

AM: In the untitled poem after “The Bells” you write about your great-grandmother describing the blast from the atomic bomb by saying “’Kira, kira,’ she said, ‘Twinkle, twinkle.’” Not only did you have to toe the line of sentimentality, but also worry about making atrocities too beautiful. How did you approach your subject matter with this responsibility in mind?

AH: This is a great question because it gets to the heart of how powerful and essential, and yet problematic, poetry of witness can be. Some people will argue that making atrocity that is beyond language somehow consumable, digestible through art, actually makes it all the more possible for atrocity to reoccur.

I can see that the poem includes beautiful language, but I think the primary drive and essence of the poem is really about the heartbreaking innocence of her phrasing, the way she must have told the story to herself. I think that may be the vocabulary she had, the language that was true to her personality and experience: to her, the bomb falling actually twinkled. And I trust readers to “get” that the poem is more about her unreplicable experience than about beautifying language for poetic effect.

Luna Luna Featuring Book Excerpt

What impressed me about this poetry collection was not only Heck’s use of imagery, but the way she gets to the heart of the matter. She shows the reader how pain is measured at different times in our life. Sometimes, pain surfaces as loss, as a strained father-daughter relationship. But, it is also a way to keep ourselves.

I admire the way Heck aligns past versions of herself and past versions of places; this collection surprised me as it is not only a collection rooted in family and history, but also one rooted in identity and the search for happiness.

In “The Leaf Book,” Heck discusses a third grade leaf-book project and in discussing school, and her father, she also delves into self-identifying. I love that line, “I know the wrong kinds of love…”

Leah Umansky

Vida Conversation with Purvi Shah

PS [Purvi Shah]: I love this idea of fruition even in years to come, because when I think back to myTerrain Tracks book launch, one of my college poet friends, Gabrielle Civil, an amazing performance artist, read as well as Kundiman co-founder, Sarah Gambito. Similarly, you had an amazing book launch for A Nuclear Family with so many voices of people who had influenced you or whose writing you admired, and I love that sense that poetry is not just a home for us individually, but is a shared, collective home. And if we can see our writing as a small way of saying, “We have voice, we have stories to tell, we take up space in this world,” we can also feel how powerful it is to do so in camaraderie. I think about how our writing pulls in our ancestors, these lineages, and simultaneously we are creating the next lineages for people to branch off from.

ANH [April Naoko Heck]: That’s part of what Kundiman taught me – there’s a level of book-learning that is simply limited and you have to experience a creative life viscerally and exchange energy with people who are living their poetry in a way you realize you want to and can. Kundiman validated that for me. Any form of creative learning has always been inextricably connected to my identity, the hardships and triumphs of my community, as someone of mixed race, a woman, descendent of war victims and survivors. And that’s not true for every Asian American female writer. That’s just my truth.