Hunger Strike

In the last part of night

of blood and memory

in the last neigh

of empty stomachs

the human tree reveals

its prophecy

and pours forth our meager

stature

Tadmor 1989

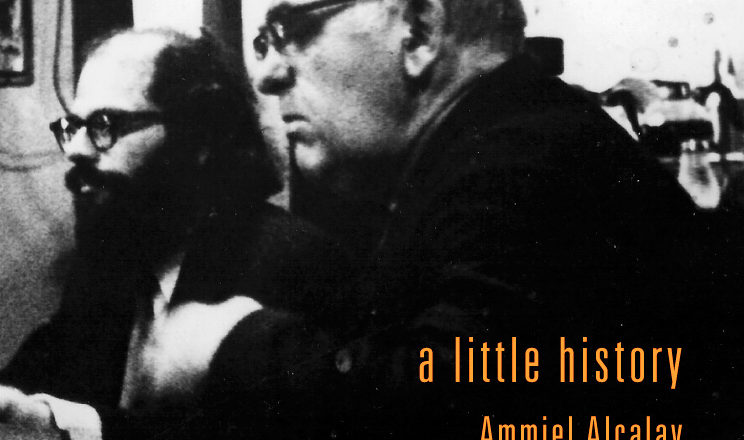

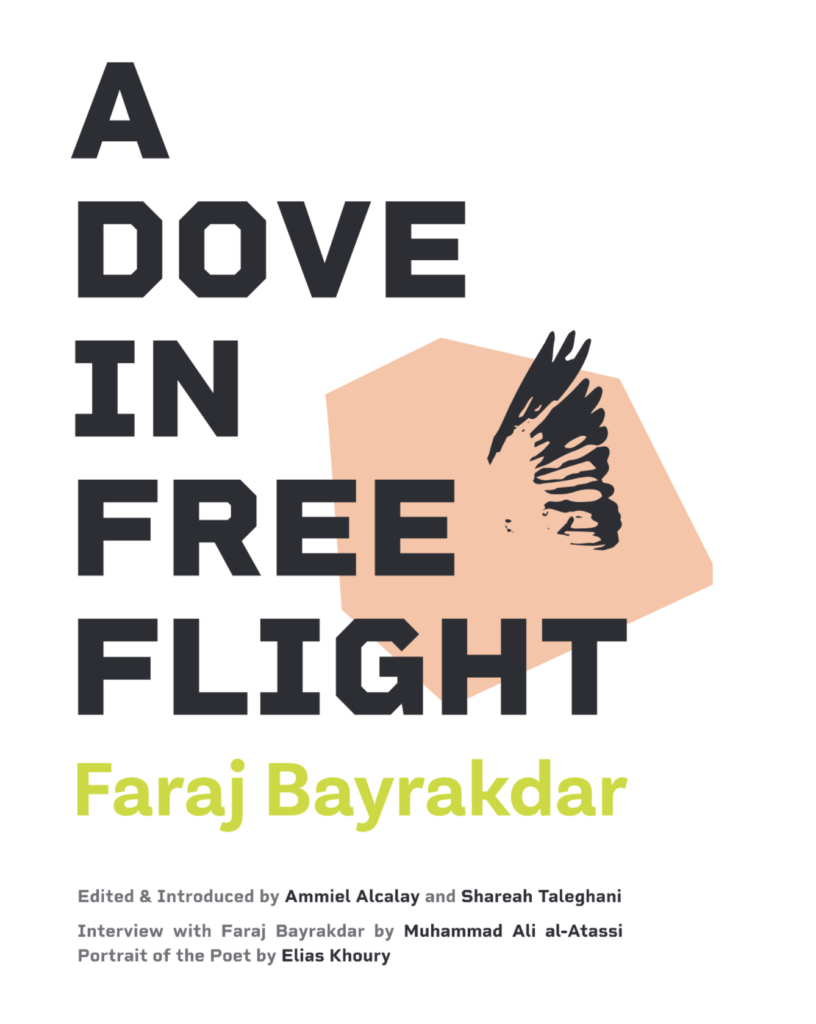

In 2002—just after 9/11 and prior to the US invasion of Iraq—a group inspired by Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury’s seminar on Arab prison literature decided to collectively translate Syrian poet Faraj Bayrakdar’s collection A Dove in Free Flight. Smuggled out of prison, the poems were published in Beirut without his knowledge, as a means of publicizing the poet’s plight as a political prisoner, and exerting pressure on public opinion to pay attention to his case. A French version, translated by the great Moroccan poet Abdellatif Laabi, himself a former political prisoner, followed.

More than fourteen years after the initial completion of the project, UpSet Press presents this extraordinary poetic, human, and historical document, featuring an introduction by editors Ammiel Alcalay and Shareah Taleghani, a preface by Elias Khoury, and a lengthy interview with the poet himself following his release on November 16, 2000, after thirteen years, seven months, and seventeen days in the Syrian carceral archipelago.

We present Elias Khoury’s introduction here, along with a selection of Bayrakdar’s poems, translated by the New York Translation Collective: Ammiel Alcalay, Sinan Antoon, Rebecca Johnson, Elias Khoury, Tsolin Nalbantian, Jeffrey Sacks, and Shareah Taleghani.

_______________________

Beautiful and intensely emotional, Faraj Bayrakdar’s songs of memory, love, heartbreak and yearning are a testimony to the transformative power of the imagination. The Syrian prisons where his poems were written remain places of torture and violence. Yet during his long years of incarceration, the poet captured the elusive bird of freedom in poems smuggled out and published in Beirut and France without his knowledge, words that went on to inspire the Syrian revolution. The impressive collective of translators, writers and critics behind this first collection of Bayrakdar’s poetry in English were inspired by Elias Khoury’s seminar on Arab prison literature at New York University, and the explosive nature of this literature in a country as closed as Syria. In an interview accompanying the poems, Bayrakdar reveals, “… captivity and freedom … enfold in themselves a charge that does not fade, not for the reader and not for the poet.”

Malu Halasa, co-editor of Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline, and author of The Secret Life of Syrian Lingerie: Intimacy and Design, and Mother of all Pigs.

_______________________

Faraj Bayrakdar’s poems, written while in prison, are a glorious testament to the power of the imagination and memory. Every page in this magnificent, important book is proof of how “language at the peak of clarity/unfolds the night,” how it transcends time and space to create its own kingdom, one where justice and love reign. Those searching for the right words to describe these turbulent days, and to offer hope, will find them here. Bayrakdar is a voice we must listen to, and this is a book that all of us must read.

Maaza Mengiste, author of The Shadow King, shortlisted for the Booker Prize

_____________________________

These searing and openhearted poems, born in prison, scrawled on cigarette paper, smuggled out from Assad’s repressive rule in Syria, and now finally translated from Arabic into English, make a fresh contribution to thought as much as to poetry. This thought is conservative in that it protects and preserves a poetics that live on under oppressive conditions. How rare it is to experience pride in being human in contrast to the depravity we have increasingly paraded in public. The prisoner, in mourning for life while that life continues outside, is the keeper of a buried treasure, thought itself and a bit of paper.

Fanny Howe, poet, novelist, and, most recently, author of Night Philosophy and Love and I.