A unique and striking fusion of poetic prose, philosophy, and stylistic acrobatics, Tractatüus Philosophiká-Poeticüus is a theoretical, mythopoetic work that uses various narrative and dramatic techniques and devices to fashion a new genre, one that is engaged with critical discourses even while it reads like a fantastical and labyrinthine story. First published in Paris in 2000 in its original English along with a suite of Parsa’s multilingual works, this bold and hallucinatory text depicts the path of writing through the deployment of a group of anonymous wanderers and a constantly metamorphosing ‘I’. With its constant reframing and reformulations, its changes of rhythms and tones, its manipulation and treatment of textual unfoldings, Tractatüus Philosophiká-Poeticüus uses the parameters and the dynamics of the reading experience, along with mythological and intertextual explorations, to construct an ingenious and beguiling treatise. The book continues to defy convenient classification and tackles, through formal and stylistic innovations, the very possibilities and limits of literature and its potential for offering new visions of the world—and new relationships to the world.

COVER BLURBS

Parsa takes us directly into the manufactory of language, the wars and revolutions where words are taken apart, their bits and pieces reassembled, here comically, there monstrously, everywhere frantically… Tractatus Theologico-Politicus: Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: Tractatüus Philosophiká-Poeticüus: Parsa’s own epic, a melding of the philosophical and the poetic, the legendary and the theological, that generates not a tractatus but a tractatüus, a vagrant genre wandering in between a dead language and one yet to be born, is a product of a total war.

From the afterword by Gregg Horowitz, Chairperson, Social Science and Cultural Studies, Pratt Institute, and Author, Sustaining Loss: Art and Mournful Life

Amir Parsa: the polyvocal defiance of the subject. His, ours, everyone’s. The polylocal embracing of not/being there… He writes for a tomorrow that will never come because ‘arrival’ is no longer among its illusions. The vertiginous gusto of his narrative is the reeling roll of that future as we can only imagine to hear it now. He seems to be teaching us how to fly—with words. His, if anything, is a post-national read, a post-categorical writing, a post-immigrant thought. He is post about anything and everything.

—Hamid Dabashi, Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature, Columbia University, and Author, Close-up: Iranian Cinema, Past, Present, Future

Few writers make more interesting globular dynamics than Amir Parsa. Under Parsa’s influence, the punctum of the pen yields islands invisibly connected beneath the water. Seen from the surface, apparently self-contained and isolated, but underneath, secretly linked in the shifting sands of a coastal shelf. Viewed from one perspective as wounds in the water, viewed from another as the beginning of healing: both views are like memory or history. True artistry emerges from and results in such perspectival shifts, allowing design and accident their ineluctable due.

—Ryan Bishop, Professor of Global Arts and Politics, University of Southampton, Author, Modernist Avant-Garde Aesthetics and Editor, Baudrillard Now

About Amir Parsa

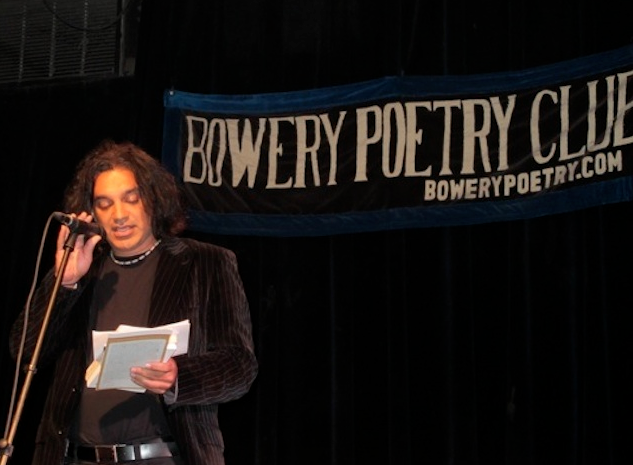

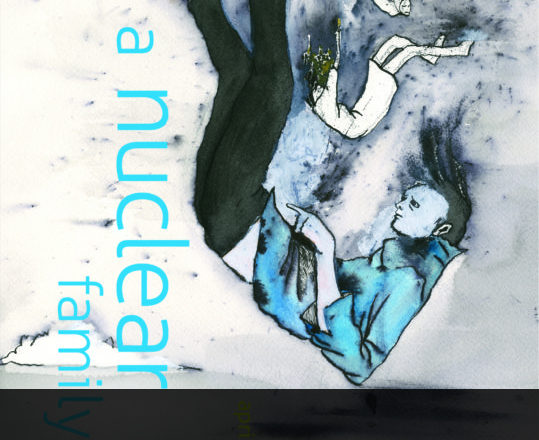

Amir Parsa was born in Tehran in 1968 and moved to the D.C. suburbs when he was ten. He went to French International schools both in Iran and in the U.S., attended Princeton and Columbia universities, and currently lives in New York City with his wife and daughter. An internationally acclaimed writer, poet, translator and newformist, he is the author of seventeen literary works, including Kobolierrot, Feu L’encre/Fable, Drive-by Cannibalism in the Baroque Tradition, Erre, and L’opéra minora, a 440-page multilingual work that is in the MoMA Library Artists’ Books collection and in the Rare Books collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. An uncategorizable body of work, his oeuvre—written directly in English, French, Farsi, Spanish and various hybrids—constitutes a radical polyphonic enterprise that puts into question national, cultural and aesthetic attachments while fashioning new genres, forms, discursive endeavors and species of literary artifacts. His writings in both English and French have been anthologized, and he has contributed to a number of print and online publications, including Fiction International, Textpiece, Guernica, Armenian Poetry Project and a mash-up issue of Madhatters’ Review and Bunk Magazine. His translations include Bruno Durocher-Kaminski’s And They Were Writing Their History, and the first two books of Nadia Tueni, which appeared under the title The Blond Texts & The Age of Embers. Since 2007, pieces and fragments from Parsa’s ongoing The New Definitely Post/Transnational and Mostly Portable Open Epic as Rendered by the Elastic Circus of the Revolution have been featured at The Bowery Poetry Club and The Riverside Church, during the Uncomun Festival, the Engendered Festival, and the Dumbo Arts Festival in New York, and at the Baroquissimo Festival in Puebla, Mexico, among other venues. This literary work is comprised of cantos and fragments constituting an on-going plurilingual epic that unfolds over time on various platforms, in multiple arenas and spaces (private and public), and through various scriptural strategies—from the traditional (handwritten sheets and books) to the new (electronic, web). In June 2010 at the Paris en Toutes Lettres festival and in conjunction with the publication of his book-length poem Fragment du cirque élastique de la révolution, he put into action The American in Paris is an Iranian in New York, a 10-hour multiplatformal ‘scriptage’ taking place throughout Paris, with fragments being simultaneously projected at the Northern Manhattan Arts Alliance during the Artstroll Festival in Manhattan. He has instigated his unique encantations, readations and bassadigas, and conducted more traditional lectures, workshops and playshops, on avant-garde poetics, literary/artistic innovation, and cultural design at museums and organizations across the world, including Norway, Mexico, Italy, France, Brazil, India and Spain. His curatorial interjections, conceptual pieces, artistic interventions, and critical educational praxis have taken place in a host of public spaces, organizations and environments. As a Lecturer, Educator and Director in The Museum of Modern Art’s Department of Education from 2004 to 2011, he developed programs, curricula, and learning experiences for a wide range of audiences. He also conceptualized and created the ongoing PinG (Poets in the Galleries) series at the Queens Museum in 2007. He has taught at Columbia, the University of Girona in Spain, and the University of Maccerata in Italy. Formerly a Chairperson and Acting Associate Dean at Pratt Institute in New York, he currently teaches at Pratt, where he is an Associate Professor and directs trans/post/neodisciplinary initiatives.

Excerpt:

And in Baabol, every night, a new tower, unlike the others but bearing an uncanny resemblance to its predecessors, sprouted in the place of the old one, razed to the ground the day before. ‘Six nights, six towers!’ exclaimed one, ‘seven nights, seven towers,’ exclaimed another! They had put into motion the question of their own death, and all was born again, constantly written, constantly traced…

The dilemma, however, was not resolved. Baabol contemplating its withering had rejuvenated itself, and now, as I remember translating the words of one, for they resonate still in my own mind, now that I myself have left Baabol, reluctantly I must add, but with all of its memories relentlessly, restlessly, clamoring through me – I shall not relate my manner of escape from Baabol, although that also would make quite a tale for the tale-teller, quite an epic for the poet! – I recall the words spoken, how the young one asked: ‘And now must we each night raze the new tower to the ground?’ The muted spectators, the muted masses, I also mute: and a silent awe echoed through Baabol, throughout Baabol, known of course, as the wondrous silence, of Baabolians.

But no one dared propose otherwise: again and again, again and again, endlessly alive, Baabolians each night razed the tower that had grown among them the night before: the towers of Baabol each night swerving from the ground: never the same tilt, never the same, unfinished, jagged-edged, endlessly windowed, the strength of an ancient monument each time: at the edge of this city, far away in the distance of all my cities, always: the Towers of Baabol…